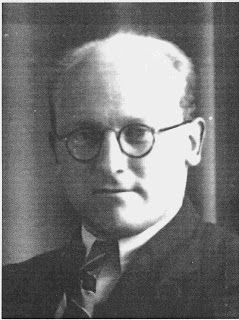

Joannes Cassianus Pompe (1901 to 1945)

Joannes Cassianus Pompe was born in Utrecht on 9 September 1901. He studied medicine at the University of Utrecht and during this time came across the symptoms of what is now known as infantile Pompe disease, which he described in his 1932 publication Over idiopathische hypertrophie van het hart. On December 27, 1930, Dr Pompe had carried out a post mortem on a 7-month old girl who had died of pneumonia. He found the enlarged heart now known to be characteristic of the infantile form of the disease and had some microscope slides prepared. These showed that the muscle tissue was distorted into an oval mesh.

He realised after detailed examination, that this appearance was due to the accumulation of something forcing the muscle tissue to distort in that way. This isn’t as obvious as it appears now – when you look at fishing net, would you conclude that it has been forced into that shape by the air filling the holes? He then tried to discover what the accumulated substance was and had the idea that it might be glycogen. Subsequent testing showed that to be the case.

Pompe was perhaps guided in that direction by his colleagues Professor Snapper and Dr van Creveld. They had published a paper in 1928 describing what is now known as Von Gierke disease, or glycogen storage disease type 1. Prior to her death the girl had been the patient of Professor Snapper. It is thought that these colleagues encouraged Dr Pompe in establishing the idea that here was a second type of glycogen storage disease, also an inborn error of metabolism. It is

Dr Pompe graduated in 1936 in the subject ‘cardiomegalia glycogenica‘, indicating that this had been a continuing subject of study for him. After a spell at the St. Canisius Hospital in Nijmegen, he was appointed as Pathologist at Hospital of Our Lady (OLCG) in Amsterdam, where he worked from June 1939 until his death

Following the fall of the Netherlands, Dr Pompe became involved with the Dutch resistance. At first he was involved in finding hiding places for Jews. Through this he made contact with the operator of an illegal transmitter.

Pompe’s laboratory was somewhat isolated from the rest of the hospital. So much so that at least two men who were hidden in the OLVG worked in the laboratory during the daytime! He therefore suggested that it would make a good hiding place for the transmitter and sometime in November-December 1944 it was installed in the animal house beneath his laboratory. The transmitter was used to send messages to the UK on behalf of the resistance.

The transmitter was eventually detected by the Germans and on Sunday 25 February 1945, at 10 am, 40-50 members of the German Military Police entered the hospital and made straight for the animal house. The wireless operator, Pierre Antoine Coronel, was broadcasting at the time and tried to resist. He was subject to summary execution in the courtyard of the hospital.

During the raid, Dr Pompe had been at Sunday mass and on returning to hospital was warned by patients of what had occurred. He went home to tell his wife that he needed to go into hiding. While leaving the house he was arrested in front of his wife and children, who were threatened with rifles.

While some of the imprisoned staff were eventually released, Dr Pompe, Louis Berben (the man in charge of the animals) and a male nurse, Piet van Doorn, were kept in jail.

On April 14, 1945, the resistance blew up a railway bridge near St Pancras, destroying an army train in the process. As a reprisal, 20 Dutch prisoners, including Dr Pompe and Louis Berben were shot. They were taken in a sealed truck to a meadow near St Pancras and, at around 9pm on 15 April, shot in two groups. The bodies were buried in a mass grave in the sand dunes near Overveen. On the same day, Piet van Doorn was also shot, in retaliation for another attack on a railway.